The Census of Population is probably the single most important statistical product a country produces. It tells governments about where to put public services and businesses where to set-up shop. It allows meaningful comparisons between and within countries in per capita terms. And among other things, the results are crucial benchmarks in a vast range of other statistics, for instance providing weights for surveys.

The headline figures also have the advantage of being relatively straightforward. Compared to other statistical constructs, the number of people who live somewhere can be understood by most. Likewise, how a population moves between Censuses is simple: population change equals natural change (births less deaths) plus net migration (immigration less emigration).

But despite the simplicity, the counting can be challenging. The Traditional Census is a count of every person in every household on a specific date. In the Republic of Ireland households are required by law to complete a Census form one night in April once every 5 years (although it was delayed in 1976 to save money, 2001 because of foot-and-mouth, and 2021 because of Covid). It’s not cheap. Census 2016 involved 4,660 enumerators delivering and collecting 2.2 million forms at a cost of €60 million. Nor are the findings timely. The labour intensity of processing the forms means preliminary statistics take several months, while more detailed data takes 1-2 years.

The other difficulty is coverage. Accuracy ultimately depends on everyone’s compliance. With people having busier lives, and with forms becoming longer (compare the Census 1961 form with Census 2022!), there have been fears that response rates will fall. This appears to be warranted given the increasing numbers of “Not-Stated” for certain questions. For example, the number not answering the Highest Education Attained question has risen from 79,000 in Census 1996 (3.3% of population who have completed education) to 199,000 in Census 2016 (6.4%).

A larger problem than missing answers is missing persons. An element of under-enumeration is to be expected. Some people have become difficult to contact – more households where all adults work; gated communities; higher levels of mobility and migration. Some may be unwilling to interact with the State – unfounded privacy concerns; undocumented migrants; illegally overcrowded accommodation. And there are undoubtedly a few who couldn’t be bothered filling out a form. Conversely there’s a risk of over-enumeration through double-counting - students living away from home; children of divorced parents - and other errors. But net under-enumeration is the likely outcome. A recent UN paper concluded that Census under-counts “should not be seen as an exception but rather as a norm”.

Statistical Offices are well-aware of these risks. The CSO take numerous measures to maximize coverage, including enumerators repeatedly visiting dwellings, language translation of forms, and publicity campaigns. If all else fails, the next step is the add (or “impute”) missing persons. The Irish form of imputation are “Reconciliation Forms” for cases where enumerators failed to collect a form from a dwelling despite evidence of occupation, with additional information “usually sourced from contacting neighbours”. According to the Quality Reports, the number enumerated this way has risen from 6,927 households (13,995 persons) in Census 2011 to 20,414 households (43,689 persons) in 2016. Thus around 1% of the population in the last Census were actually manually counted by enumerators.

Other countries take further steps. Most developed countries who undertake a Traditional Census carry-out a “Post-Enumeration Survey” afterwards and compare the results. An example is England and Wales’s “Census Coverage Survey”. Another corrective is a “Demographic Analysis”, which checks whether totals are plausible given records in administrative data (e.g. school enrollments) and vital statistics (number of births in a year). Using some of these methods have resulted in estimated net under-counts of 1.0% in Australia (2016), 2.4% in Canada (2016), 6.1% in England & Wales (2011), and 7.1% in New Zealand (2013). The circumstances and the techniques here differ, so they are not strictly comparable.

(Of course in an age of declining voter turnout and public trust in institutions, it could be said that well over 90% compliance rate in the Census is an achievement!)

Alternative Censuses

At least partly because of these issues (cost, coverage, and timeliness), the Republic of Ireland is one of the last Western European countries to carry out a Traditional Census. In 2010/11 Luxembourg, Greece, Portugal, and the UK were the only other EU15 states. Indeed Europe is now something of a “demographic laboratory”. France has innovated a Rolling Census of continuous surveys instead of one big count. The main alternative is based around a national Population Register, which were pioneered to count populations by the Nordics from the 1960s.

Most countries now use registers, other administrative sources, and surveys to count Census-like population counts. These methods do not remove under and over-count problems. The latter may be most problematic, particularly with migration, as it requires emigrants to be de-registered and internal migrants to be re-registered. For more detailed information the public sector data may be out-of-date or be incomplete. The other downside is a loss of privacy. It would require National ID cards, which arguably has little political or public support in Ireland.

A full list of how countries counted or plan to count their populations in the international Census Round of the early 2020s is available here.

Official Annual Population Estimates

An advantage of Population Registers is that it’s possible to regularly compute population counts instead of providing one number every few years. Annual Population Estimates are required for years in-between Censuses, which come with their own margins of error. The CSO applies a “component method”, where annual estimates are determined by natural change (from birth and death registrations) and net migration (from estimates). Because vital statistics records tend to be reliable, the revisions listed in the table above were because of migration. Again to stress the centrality of the Census, all annual estimates are anchored in how many people are enumerated every 5/6 years. The estimates change to suit the Census, it’s never the other way round.

Estimating has become more difficult given the increasing flow of people in-and-out of Ireland, with annual immigration typically at 2% of population. A further complication is that the estimates are on a “usually resident” (or “de jure”) basis - in other words people who live or intend-to-live in the country for over 12 months. The PPSN (an Irish ID number) allocation statistics highlight significant short-term immigration that is not accounted for in the annual estimates. (Note: in the Census publications there’s also a “de facto” population, which should include all tourists and visitors present on Census Night - i.e. people who are not usually resident. The de facto population is always a bit higher than the de jure, but the latter is normally used as it’s more relevant for policymakers and the like).

Historically the CSO estimated net migration by passenger movements recorded at airports and ports. This ran into difficulty in Census 1979, which showed a sizable under-estimate of the population, mainly because of return migration of the 1950/60s emigrants to Britain. Interestingly, in contrast to recent revisions, the 1979 revision caused a fair deal controversy, see an article by the late Gerry Hughes. It has gradually been amended to include estimates from the Labour Force Survey, and administrative data from home (PPS Numbers allocations) and abroad (Australian Visas, UK National Insurance Numbers allocations). Nevertheless, the last two Censuses showed net migration was under-estimated by 90,600 in 2011 and 65,900 in 2016. Revisions for 2017-2021 will have to wait for Census 2022.

Early Experimental Population Estimates

Unlike most European countries, the Republic of Ireland does not have a Central Population Register. But it does have a unique (and pseudonymous-able) identity number: the PPS Number. With this identifier it has been possible to make estimates using administrative-data (e.g. from Education, Revenue and Social Welfare records). A “Signs of Life” approach can be used, where activity directly or indirectly with public sector bodies is used as evidence of residence. In December 2021 the CSO released their first published estimate in a research paper from Irish Population Estimates from Adminstrative Data Sources (IPEADS) project. Previous work can be found in a paper by John Dunne, which found that estimates using admin data were higher than Census 2016.

The release may have been motivated by the difficulties outlined above, but the greatest nudge was probably new EU regulations that will require the CSO to produce more timely demographic statistics. This will require using administrative sources. It should be noted that the data cited below are experimental and subject to revision. One issue is that people who had no interaction with the state may not be included. But there’s obviously potential for over-counting. As such the CSO are at pains to point out that “particular care must be taken when interpreting the statistics” and they “should be used with caution”.

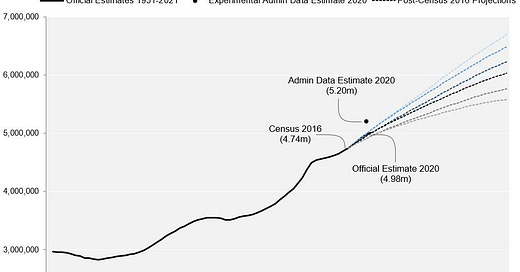

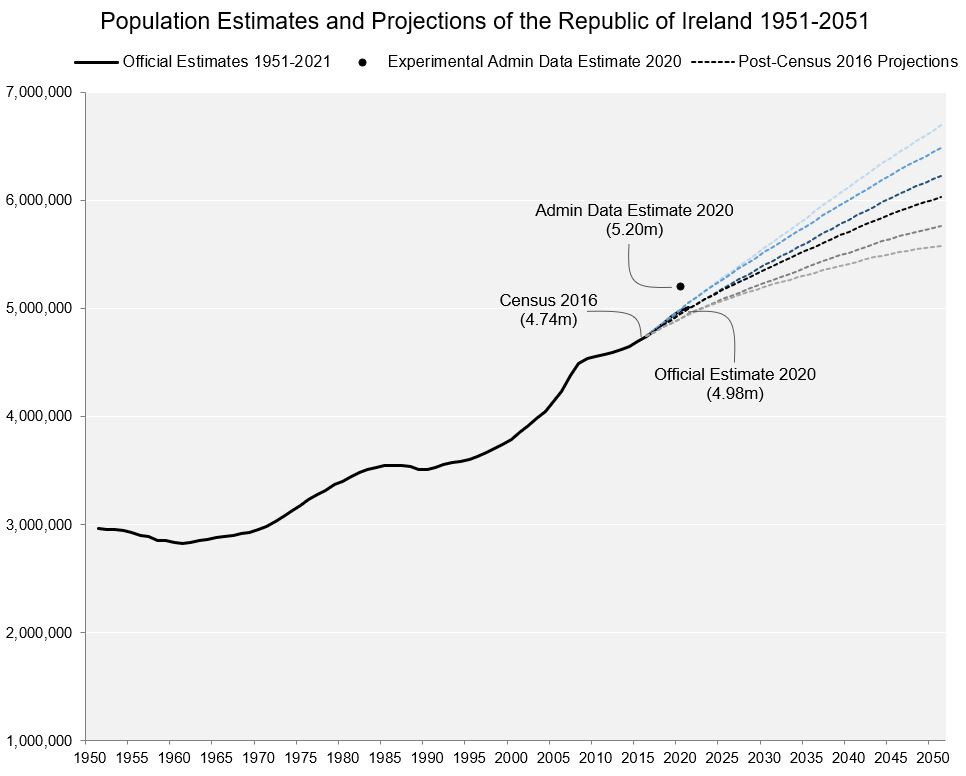

The experimental methodology suggested that 5.20 million people were resident in the Republic of Ireland in April 2020, based on administrative data in a 12-14 month time-period. This is 4.5% higher than the 4.98 million in the official estimates (pre-Census 2022 revision). Applying different rules resulted in different totals. There were 5.48 million people who had interaction with public sector bodies in the time-period, but some would have been temporarily residents. Narrowing the time-period produced a smaller estimate of 5.06 million people, although this may be too exclusionary given some databases have a lag. (And it implies that there are nearly half a million short-term migrants and emigrants annually). Whether estimates were biased because of pandemic would be another consideration. Though it’s worth noting that high and low estimates are not unusual for alternative Census-like counts.

With all caveats in mind, comparing the experimental and official estimates reveals that the difference was mainly among the working-age population and younger adults. There were 47,000 more 20-somethings and 81,000 more 30-somethings in the administrative data. There were more males (+144,000) than more females (+82,000). The difference between administrative data and Census/official estimates among children and older people was small, with small exception of 5-9 year olds (+10,000).

This may be reassuring as these age-groups are most dependent on public services. However, clearly an additional quarter-of-a-million people would require housing and infrastructure. If the experimental estimates are accurate it would mean that the Republic of Ireland’s population in 2020 was already at a level that was forecast for the end of the decade (see graph at the top). This would have implications for public planning (e.g. Project Ireland 2040) which rely on official projections.

As well as being primarily of working-age, the difference was mostly among those with a migrant background, with Irish-Nationals (+42,000) and Foreign-Nationals (+184,000). The table above compares Eurostat’s detailed population data for 1 January 2020 with the CSO’s experimental data for mid-April. (No detailed nationality data is available for CSO’s April official estimate, but obviously the differences are small). There were higher populations among nationals from Brazil, Croatia, India and Romania, which are the countries with highest PPS Number allocation trends in recent years. Though the extra British nationals is surprising. Some of the main immigrant nationalities from pre-2008 crash actually showed small declines, notably Nigeria and Poland. A drawback with using admin data is that people who are now naturalized Irish citizens may be still recorded with their old nationality. As mentioned government data can be less up-to-date than a self-assessed data.

Another comparison available is by locality based on geocoded data. The largest absolute contrast was Dublin (+73,000), but in percentage terms it was similar in Midlands, Mid-West and South-East. Disparities were perhaps more regionally spread out than would be expected. If accurate it might put less strain on the housing system than if it was concentrated in certain areas. Though the annual population estimates are not dis-aggregated by county, so comparison of the main metropolitan areas was not possible.

A final note concerns the Principal Economic Status. The experimental data suggests a labour force of 2.74 million in April 2020, of which 2.40 million were at work and 340,000 unemployed. In comparison the Labour Force Survey estimated a labour force of 2.46 million (2.35 million at work and 115,000 unemployed) in Q1 2020 and 2.26 million labour force (2.14 million at work and 120,000 unemployed) in Q2 2020. The discrepancy of unemployed - and possibly the labour force - can partly be explained by different definitions: experimental is based on number receiving Social Welfare payments while LFS is based on the stricter ILO criteria. Similarly there is always a higher self-reported unemployment figure in the Census.

The CSO’s methodology states that ascertaining people’s economic status from the admin data is “challenging”. And then there’s Covid-19. The experimental data includes the early pandemic payments. In theory there should be no great errors or over-counting as it’s all by PPSN, but practice may be different. Yet assuming the working-age population under-estimate is accurate, then it would surely imply a larger labour force than previously thought. An additional 4.5% of people is manageable and probably not entirely surprising. But an around 10% increase in the labour force would change numerous statistics from productivity to wages. Revisions could be greater in certain sectors. Another important question for the future is How Many People Work in Ireland?

To reiterate, the experimental estimates should be treated with caution. The methods and the underlying sources are both subject to change. They could revise the population down as well as up. And the more granular the data the more caveats that need to be applied. That said, it’s worth nothing that statistics will rely more on administrative sources in the near future. Comparisons between old and new methodologies will become more frequent. It’s entirely possible that the start-date of certain time-series will have to be reset. Even the Census may be changed. There is an ambitious plan for Census 2031 to be based only “administrative data and a large-scale survey”. In the mean time, the CSO plan to carry-out a detailed comparison of Irish population estimates in Census 2022 (preliminary results are due 24 June).

It remains to be seen whether these estimates are non-census.

Testing, testing, 1, 2, 3...

Dear John, have you seen my tweet?

You posted data, and I asked you to share a source...